A Brief History of Film

by Fr. John Wykes, OMV

Part One: Muybridge and His Trotting Horse

To think the medium that produced such screen gems as David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia or Hayao Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron began with a barroom bet seems so outlandishly vulgar as to be unbelievable. At yet that is how it happened – at least that’s what some people say.

It seemed simple enough – even for brains sufficiently dulled by a few drinks. The question was – when trotting, does a horse ever have all four hooves off the ground at the same time? Some said no. Others, including Eadweard Muybridge, said yes. He went about to prove his point using one of the most amazing technological advancements of the 19th Century – photography.

It was a summer day in 1878 when Muybridge set up his cameras, twelve of them, along the side of a racetrack. Each camera had electrical wires extending across. As the now-famous horse, Occident, trotted by, it tripped the wires which tripped the shutters. Muybridge now had twelve still pictures of Occident trotting -- and proof that a horse can have all four hooves off the ground at the same time.

But this was just the beginning. Muybridge soon discovered that the photographs, when passed by the eye in rapid succession, ceased to resemble separate images and became a “moving” image. It was an amazing illusion – and not really a new one. The French has developed the phenakistiscope back in the 1830s. It provided drawn images that, when projected correctly, gave the entertaining illusion of motion. Now with the advent of photography plus the capability of taking more than one photo in succession, the animation toys of yore suddenly became much more powerful, with fully realized actual photographic images of animals and people coming to life in a way that had never been possible.

Muybridge made the study of motion his life-long work, creating innumerable short “motion pictures” of animals, men, women, acrobats, athletes, and dancers. By the time of his death in 1904, Muybridge had secured his place in film history.

Part Two: The Original Tik Tok and Instagram – Lumiere, Edison, and Glimpses of Everyday Life

A young gymnast does a flip. Workers leave the factory. A train arrives at the station. A couple shares a passionate kiss.

Such brief “movies,” sometimes only seconds in length, are common in our own 21st Century. Perhaps such social media apps as Instagram, Tik Tok, or YouTube Shorts come to mind. But the idea of being entertained by brief clips is decidedly old school.

Very old school. Extremely old school.

For this approach to visual storytelling is actually a throwback to the very beginning of movies. Each example that I mentioned in the first paragraph is from the 19th Century – films made 130 years ago.

Things have really come full circle, haven’t they?

In the beginning, of course, brief “tests” like these were all that was possible. And necessary. People were amazed by these life-like photographs that moved. Others were aghast at this latest technology which showed ghostly moving images in silence and, even worse, in a strange colorless world of blacks, whites, and greys.

But it was the “amazed” crowd that won the day and people in general couldn’t get enough of these thrilling glimpses.

In France, the Lumière Brothers created an amazing process by which a film base was covered with photographic emulsion and then perforated, allowing the film to be advanced one frame at a time past the aperture. The brothers took their new device out into the streets – capturing everyday events that wowed audiences. Workers Leaving the Factory (1895) and Baby’s Breakfast (1895) were amazing enough.

But it was their Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat Station (1896) which created film history when audiences, thinking that the hyper-realistic images of a photographed train would run them over, reportedly ran to the back of the theater, fearing for their lives. Some modern critics doubt the truth of this story. I do not. We need to remember that for people in those days, seeing a Lumiere film projected on screen in the 19th Century had the same impact as us watching a display on The Sphere in Las Vegas in the 21st Century. In each case, the technology was showing a clarity and realism that had never been seen before.

Over in the USA, inventor Thomas Edison and his assistants were busy creating their own movie magic. Fred Ott’s Sneeze (1894) is my favorite. With a sprightly running time of five seconds, the film shows Fred Ott (one of Edison’s assistants) sneezing for the camera.

Unreeling at a truly epic running time of eighteen seconds, The Kiss (1896) shows performers May Irwin and John Rice, well, kissing. Many critics denounced the film as obscene, most especially since the couple is presented in closeup (extremely rare for the time) and is shown kissing three times – not just once. One reviewer called the work “disgusting”. Audiences didn’t seem to mind too much, and many such similar films were produced over the next several years.

Nowadays, youngsters from Generation Z and Generation Alpha post and share short five-second or ten-second clips of plane turbulence, funny pet tricks, and physical feats of strength – convinced that they have revolutionized the way moving images are captured and edited. But all they have done is reverted to old school ways of filmmaking. Very old school.

But the story doesn’t end there. What is neat is that some of these younger people have rediscovered the films of yore and have re-posted them – many times using colorization and a higher frame rate to enhance the picture. Because of this, Lumiere and Edison have found new audiences, so that even that passionate kiss from 1896 and Fred Ott’s wonderful sneeze are being shared on Tik Tok, Instagram, and YouTube Shorts.

Things have really come full circle.

Part Three: “Once Upon A Time” – The Movies Become Stories

I was watching a Tik Tok video recently of a weightlifter going over the proper way to do a bench press. The video was noteworthy because it was longer than just 10 or 15 seconds, but more like 45 seconds or a full minute. One viewer commented, “Wow, a TikTok video that actually has a beginning, a middle and an end. What a refreshing change of pace!”

I had to laugh. The sentiment could have been expressed with equal fervor back in 1903 – when the first film with a story was released.

But I digress.

Actually, there were a number of films released before 1903 that had something resembling a plot. Georges Méliès, the French magician filmmaker who wowed audiences with his beautiful visual effects, filmed the story of Joan of Arc in 1900 and sent men to the moon in 1902. Granted, these films were short and primitive. But they did tell a story and had the semblance of a plot.

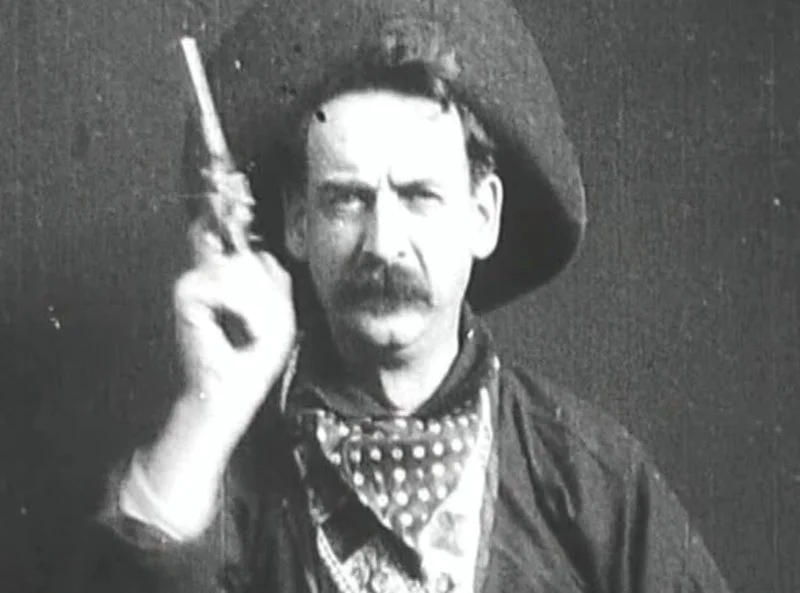

It is The Great Train Robbery (1903) that gets all the attention and all the credit. Directed by Edwin S. Porter, the film told the story, using multiple shots from various angles, of a train robbery. With a gargantuan running time of 12 minutes, the movie had suspense, drama, action, and even an unforgettable final shot of a gun being fired directly at the camera.

The language of film was being created quickly. But lessons were often learned the hard way.

Take, for example, Life of an American Fireman (1903), also made by Porter, which depicts a fireman rescuing a woman and her baby from a burning building. Porter wanted to get inventive and show the event from multiple angles. In the final film, we first have a shot from the inside. The woman and the child are in the room as the fireman enters and rescue them. Then we have a shot from the outside. We see the fireman climb up the ladder to the window, disappear inside, then reappear outside with the woman and then the child. Motion pictures being as unique as they are as a visual art form, including not only the dimensions of space but also of time, it became obvious, only in hindsight, that it made no sense to have the same event presented twice, from beginning to end.

It was only years later that others re-edited the sequence in a way that made sense – first we have a shot from the outside and see the fireman enter the house. The we cut to the inside shot of the woman and child in the house and the fireman enters to rescue them. Then we cut back to the outside of the house to see the fireman carry both the woman and the child to safety. This was the first example of cross cutting – something we take for granted today but was completely new back in the early 1900s.

As the language of film developed, the desire to create grander stories, even epics, took hold of these first moviemakers. We learn about the silent movie masterpieces of the 1910s and 1920s in our next article.

Part Four: D.W. Griffith and the Birth of Epic Cinema

As cinema moved into the 1910s, a powerful film “industry” formed, most famously among the orange groves of Hollywood in California. Armed with great ambition and a lot of money, the young powerhouses of this fledgling industry sought to expand film to epic proportions. In doing so, one prominent director not only made a lot of money but, in the process, helped to create the language of cinema.

Famous for his extravagant cinematic vision and his extravagant spending, D.W. Griffith stunned America with The Birth of a Nation (1915). Unreeling at a truly epic running time of over three hours, the film was controversial (and remains so to this day) for its revisionist depiction of slavery and the presentation of Ku Klux Klansmen as the “heroes” of the climactic scene. It was an enormous financial success – inspiring the expenditure of even more money on bigger films.

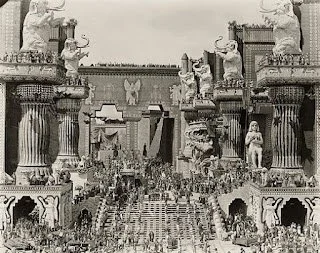

Griffith followed up Birth of a Nation with a more extravagant production the very next year. Entitled Intolerance (1916), the monstrous thee-hours-plus epic intercut different stories from four different time periods – the Passion and Death of Jesus Christ, a story of crime and struggle in modern-day (1910s) life, the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, and the Persian defeat of the Babylonian Empire. That last segment was the most famous, featuring thousands of extras parading down the largest set ever built for a film. Well received by critics and audiences alike and weighed down by its $2 million budget, Intolerance just barely made its money back.

It was Griffith who, along with Mary Pickford, Charles Chaplin, and Douglas Fairbanks, decided to unite forces, providing the artists an opportunity to make their own films without having to follow the dictates of industry producers. These artists, united in their desire to create, called their joint venture company…what else? United Artists.

Chaplin himself got into the epic game – an extraordinary feat for one with such rough beginnings. A native of London, Chaplin’s father was a music hall performer who drank himself to death, while his mother, cracking under the pressure of raising Charlie and his half-brother Sydney, had to be sent to a mental asylum. By the age of 14, Charlie Chaplin was living like an orphan but was extremely talented – very popular for his comedic routines on stage. By the age of 19, he was working with Fred Karno – a connection that sent him on a boat to the States (with fellow passenger Stan Laurel who would also become a great comic). Eventually arriving in California, he created The Tramp character that made him famous. By the time he co-founded United Artists in 1919, Chaplin was said to be the world’s most recognizable figure (more so than the president or the pope).

His “epic” was inspired by historic images of prospectors traveling West seeking gold. The resulting film, The Gold Rush (1925), accomplished what most thought was impossible – extending a film comedy to a feature-length running time. Chaplin managed to do this by mixing in pathos with the comedy – the alternating currents of emotion are what helped to move the story forward and entertain audiences. His film ended up making an enormous amount of money.

The film epic was not limited to America. In France, Abel Gance envisioned making six enormous epics based on the life of Napoleon Bonaparte. He made only the first film. Stretching the limits at a truly astonishing running time of five and a half hours, Napoleon (1927) featured innovations such as hand-held camera, multiple exposures, gib shots, split screen, and film tinting. For the film’s finale, three projectors roared to life, presenting a kaleidoscope of individual images or a single panorama. Due to the difficulty of presenting this colossal epic, Napoleon remained relatively unknown until film archivist Kevin Brownlow restored it and brought it to new generations of audiences during the 1980s and beyond.

Meanwhile, over in Russia, young filmmakers were experimenting with editing, creating montages of unprecedented rapidity and depth of meaning. Soviet montage editing is covered in our next article.

Single frames from various shots from the famous Odessa Steps Sequence (Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin {1925})

Part Five: Splicing, Dicing, and the Birth of Montage Editing

by Fr. John Wykes, OMV

Not long ago I was having a conversation with a young filmmaker. My friend was anxiously trying to make a distinction between how Baby Boomers and Gen Z’ers edit. He was trying to make the point that editing in the 21st Century is at a much faster pace than it was in the past. So I showed him a clip from a 100-year-old film. As he watched the rapid-fire editing montage, his mouth dropped open and he said, “Wow”.

The more things change, the more they remain the same.

As I have told my film students many times before, it is the content and not the year that determines the pace of editing. Some will start with the technique and work backwards to the content – for example, saying “I want to make a really cool fast-paced video” and then trying to figure out what content to force into their pre-conceived editing schema. The better way is to decide on the content first and then let the content determine the pace of the editing.

That said, some of the fastest editing from the 20th Century can be found in the silent era – a time when the visual image danced free from the constrictive grip of synchronous sound.

The filmmaker often credited with discovering the true power of montage editing is Sergei Eisenstein. Hardly a Gen-Z’er, Eisenstein was born back in 1898 and boasted a head of hair that looked as jarring as his editing. A product of his time, this Latvian filmmaker and theorist made movies filled to the brim with Soviet propaganda. His images, if you can stomach the Soviet-style preachiness, are as powerful today as they were over one hundred years ago.

Eisenstein discovered the power of editing when he realized that two shots, each with very different content, could create a whole new meaning when spliced together. This can be summarized by the formula:

Shot A + Shot B = Meaning C

…in which the juxtaposition of Shots A and B create a new meaning (C) that cannot be found in Shot A alone or Shot B alone.

Take, for example, the opening post-title shots of Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times (1936). A shot of a flock of sheep going past the camera (Shot A) slowly dissolves into a shot of workers walking from a subway station on their way to work (Shot B). The meaning we find in this juxtaposition, which is not found in either Shot A alone or Shot B alone, is that workers in our modern world have been dehumanized; they are nothing more than mindless sheep at the service of modern machines. Of course, Charlie gets drawn into the gears of a machine later on in the film – he is, in a sense, “devoured” by modern technology.

Lev Kuleshov made a famous film in which the shot of an actor was juxtaposed with a bowl of hot soup, a dead child lying in state, and a scantily-clad female. The shot of the actor was identical each time but the actor’s performance appeared to depict hunger, sadness, or lust, depending on the shot with which it was combined.

Eisenstein took this concept of shot juxtaposition and pushed it to the limit, experimenting with ever more rapid editing and shots lasting a fraction of a second.

His best-known work, Battleship Potemkin (1925) features two memorable sequences. One – the plate-smashing sequence shows the growing frustration of a sailor who has had enough of hunger and smashes a plate in a flurry of brief shots (I counted ten shots in four seconds). Two – the Odessa Steps sequence shows the slaughter of innocent people by Cossacks marching down on them with guns and bayonets. Easily the best-known scene in silent cinema, the Odessa Steps sequence has been referenced countless numbers of times in other films – most famously in Brian de Palma’s The Untouchables (1987), which even goes so far as to show a baby carriage tumbling down the stairs, just as in Eisenstein’s film.

Convinced of the power of montage editing but taking a more documentary approach, filmmaker Dziga Vertov turned his camera to real people and events to create his Man with a Movie Camera (1929). In this amazing film, Vertov uses dutch angles, split screen, slow motion, fast motion, and a dizzying array of other techniques to capture real people in real life circumstances. Firefighters racing to a fire are real firefighters. Athletes running in a race are real athletes. Telephone operators busily flipping switches and connecting cables are real telephone operators. Vertov takes these bits of reality and cuts between them with amazing dexterity – sometimes the pace of editing is so fast as to be almost hypnotic.

What made all this possible one hundred years ago was that these films were silent. Perhaps we should be more specific, because silent films were never truly silent – there was always music (and even some sound effects) that accompanied each film. What was technically impossible at the time was synchronous sound – for example, dialogue that matched the lip movements of the performers on screen.

In his early years, Eisenstein saw a lack of synchronous sound not as a negative, but as a strong positive. No synchronous sound meant that the visual image was released from bondage. It did not have to slavishly link itself to sound as in a theater production. Instead the visual image, accompanied only by music, could be cut, cross cut, dissolved, sliced and diced, even down to a fraction of a second, with a freedom that was impossible in most other art forms.

With the passage of time, the coming of sound films was inevitable. Cameras became heavy – monstrosities that were blimped so the loud motors would not interfere with on-set sound recording. The radical editing of Soviet montage gave way to a more bland and realistic pace which allowed lengthy exchanges of dialogue to take place. The inventiveness of silent cinema gave way, at least for a time, to a more programmatic approach. Not until Alfred Hitchcock lensed his famous shower sequence in Psycho (1960) did cinema regain the radical inventiveness it had lost with the end of the silent era.

Part Six: The Early Sound Era and the Advent of Technicolor

by Fr. John Wykes, OMV

My mother was only six years old when The Jazz Singer (1927) was released. She recalled how her older sister burst into the house one evening, so excited from her trip to the movie theater. “Oh mother!” she exclaimed, “On the screen was Al Jolson! Then he opened his mouth – and out came a voice!”

The movie was mostly silent and only a couple of songs were given the synchronous sound treatment. But history had been made and there was no going back. Similar to the digital quandary of several decades later, the new technology initially created confusion and competition among competing formats.

Now getting precariously close to middle age, Charles Chaplin was the solitary hold out, convinced that “talkies” would ruin the magic of his Tramp character. Not that the sound enthusiasts didn’t try. They most certainly did, with one company sending Al Jolson himself to the Chaplin Studios in a highly publicized effort to sway the famous comedian. But when City Lights was released in 1931, it was not only silent but actually went on to mock synchronous sound in its opening scene. It became one of Chaplin’s great masterpieces and guest of honor Albert Einstein was said to cry when viewing the film’s emotional conclusion at the gala premiere. After Modern Times (1936), Chaplin finally gave in and left the silent era forever, making only sound films from then on.

Another technological breakthrough was the advent of color. This great achievement came at a price. Not only did sound force cameras into blimps, cutting down on the ability to move the camera freely, but the new color technology added further limitations to camera movement. Technicolor required three rolls of film running simultaneously with each strip of film registering a different primary color. The Technicolor cameras therefore had to be much larger than their black-and-white counterparts. When fully blimped (to cut down on all the camera noise to help with sound recording), these monstrous cameras could weigh up to two hundred pounds.

The studio system was in full swing and stars were signed to specific studios. The new technology of both sound and color allowed for more spectacular offerings and for greater star power for their actors.

Often called the greatest year in the history of cinema, 1939 saw the release of The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Stagecoach, Goodbye Mr. Chips, Wuthering Heights, and Gunga Din, along with two of the most famous films of all time, Gone with the Wind and the Wizard of Oz.

None of this came easily. Wizard of Oz is famous for its behind-the-scenes nightmares, including the aluminum dust allergy that sent original Tin Man actor Buddy Ebsen to the hospital, and the fire accident that burned Wicked Witch actress Margaret Hamilton so badly she was hospitalized for six weeks. Gone with the Wind is famous for both its high budget scenes and its dizzying array of multiple directors. Both films made enormous sums of money, spurring the studios to continue churning out their lavish productions.

World War II enveloped the globe. It was at this time that a young Orson Welles was preparing to turn the world of cinema upside down. Welles and other brash young filmmakers of the 1940s and 50s will be discussed in the next article.