A Brief History of Film

Part Three: “Once Upon A Time” – The Movies Become Stories

by Fr. John Wykes, OMV

I was watching a Tik Tok video recently of a weightlifter going over the proper way to do a bench press. The video was noteworthy because it was longer than just 10 or 15 seconds, but more like 45 seconds or a full minute. One viewer commented, “Wow, a TikTok video that actually has a beginning, a middle and an end. What a refreshing change of pace!”

I had to laugh. The sentiment could have been expressed with equal fervor back in 1903 – when the first film with a story was released.

But I digress.

Actually, there were a number of films released before 1903 that had something resembling a plot. Georges Méliès, the French magician filmmaker who wowed audiences with his beautiful visual effects, filmed the story of Joan of Arc in 1900 and sent men to the moon in 1902. Granted, these films were short and primitive. But they did tell a story and had the semblance of a plot.

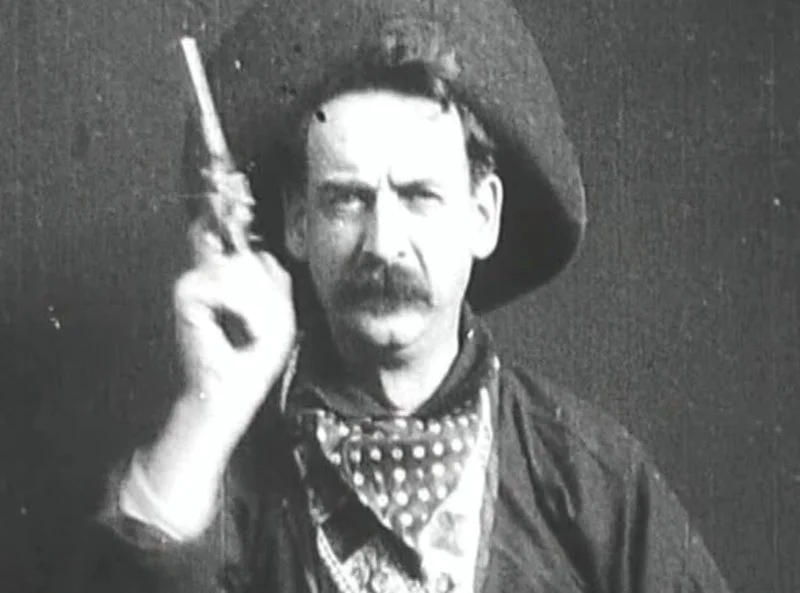

It is The Great Train Robbery (1903) that gets all the attention and all the credit. Directed by Edwin S. Porter, the film told the story, using multiple shots from various angles, of a train robbery. With a gargantuan running time of 12 minutes, the movie had suspense, drama, action, and even an unforgettable final shot of a gun being fired directly at the camera.

The language of film was being created quickly. But lessons were often learned the hard way.

Take, for example, Life of an American Fireman (1903), also made by Porter, which depicts a fireman rescuing a woman and her baby from a burning building. Porter wanted to get inventive and show the event from multiple angles. In the final film, we first have a shot from the inside. The woman and the child are in the room as the fireman enters and rescue them. Then we have a shot from the outside. We see the fireman climb up the ladder to the window, disappear inside, then reappear outside with the woman and then the child. Motion pictures being as unique as they are as a visual art form, including not only the dimensions of space but also of time, it became obvious, only in hindsight, that it made no sense to have the same event presented twice, from beginning to end.

It was only years later that others re-edited the sequence in a way that made sense – first we have a shot from the outside and see the fireman enter the house. The we cut to the inside shot of the woman and child in the house and the fireman enters to rescue them. Then we cut back to the outside of the house to see the fireman carry both the woman and the child to safety. This was the first example of cross cutting – something we take for granted today but was completely new back in the early 1900s.

As the language of film developed, the desire to create grander stories, even epics, took hold of these first moviemakers. We learn about the silent movie masterpieces of the 1910s and 1920s in our next article.

Note: After two weeks, this article will be archived under “A Brief History of Film” which can be located under “Articles, Essays, Blogs, and More” from the main menu.