A Brief History of Film

Part Four: D.W. Griffith and the Birth of Epic Cinema

by Fr. John Wykes, OMV

As cinema moved into the 1910s, a powerful film “industry” formed, most famously among the orange groves of Hollywood in California. Armed with great ambition and a lot of money, the young powerhouses of this fledgling industry sought to expand film to epic proportions. In doing so, one prominent director not only made a lot of money but, in the process, helped to create the language of cinema.

Famous for his extravagant cinematic vision and his extravagant spending, D.W. Griffith stunned America with The Birth of a Nation (1915). Unreeling at a truly epic running time of over three hours, the film was controversial (and remains so to this day) for its revisionist depiction of slavery and the presentation of Ku Klux Klansmen as the “heroes” of the climactic scene. It was an enormous financial success – inspiring the expenditure of even more money on bigger films.

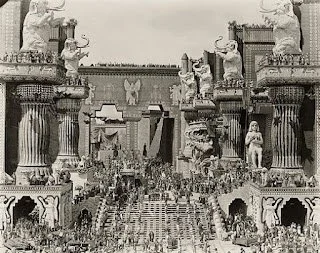

Griffith followed up Birth of a Nation with a more extravagant production the very next year. Entitled Intolerance (1916), the monstrous thee-hours-plus epic intercut different stories from four different time periods – the Passion and Death of Jesus Christ, a story of crime and struggle in modern-day (1910s) life, the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, and the Persian defeat of the Babylonian Empire. That last segment was the most famous, featuring thousands of extras parading down the largest set ever built for a film. Well received by critics and audiences alike and weighed down by its $2 million budget, Intolerance just barely made its money back.

It was Griffith who, along with Mary Pickford, Charles Chaplin, and Douglas Fairbanks, decided to unite forces, providing the artists an opportunity to make their own films without having to follow the dictates of industry producers. These artists, united in their desire to create, called their joint venture company…what else? United Artists.

Chaplin himself got into the epic game – an extraordinary feat for one with such rough beginnings. A native of London, Chaplin’s father was a music hall performer who drank himself to death, while his mother, cracking under the pressure of raising Charlie and his half-brother Sydney, had to be sent to a mental asylum. By the age of 14, Charlie Chaplin was living like an orphan but was extremely talented – very popular for his comedic routines on stage. By the age of 19, he was working with Fred Karno – a connection that sent him on a boat to the States (with fellow passenger Stan Laurel who would also become a great comic). Eventually arriving in California, he created The Tramp character that made him famous. By the time he co-founded United Artists in 1919, Chaplin was said to be the world’s most recognizable figure (more so than the president or the pope).

His “epic” was inspired by historic images of prospectors traveling West seeking gold. The resulting film, The Gold Rush (1925), accomplished what most thought was impossible – extending a film comedy to a feature-length running time. Chaplin managed to do this by mixing in pathos with the comedy – the alternating currents of emotion are what helped to move the story forward and entertain audiences. His film ended up making an enormous amount of money.

The film epic was not limited to America. In France, Abel Gance envisioned making six enormous epics based on the life of Napoleon Bonaparte. He made only the first film. Stretching the limits at a truly astonishing running time of five and a half hours, Napoleon (1927) featured innovations such as hand-held camera, multiple exposures, gib shots, split screen, and film tinting. For the film’s finale, three projectors roared to life, presenting a kaleidoscope of individual images or a single panorama. Due to the difficulty of presenting this colossal epic, Napoleon remained relatively unknown until film archivist Kevin Brownlow restored it and brought it to new generations of audiences during the 1980s and beyond.

Meanwhile, over in Russia, young filmmakers were experimenting with editing, creating montages of unprecedented rapidity and depth of meaning. Soviet montage editing is covered in our next article.

Note: After two weeks, this article will be archived under “A Brief History of Film” which can be located under “Articles, Essays, Blogs, and More” from the main menu.