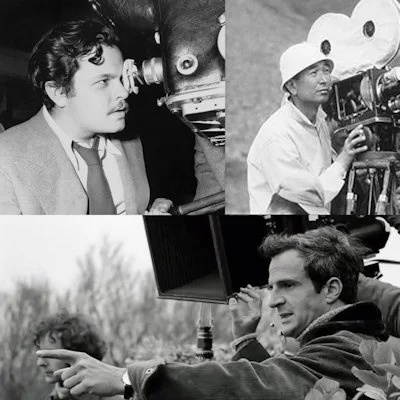

Filmmakers, going clockwise starting from upper left: Orson Welles, Akira Kurosawa, and Francois Truffaut.

A Brief History of Film

Part Seven: From Kane to Cannes and Beyond – New Filmmakers Leave Their Mark

by Fr. John Wykes, OMV

Born in Kenosha, Wisconsin, Orson Welles was hailed as a child prodigy almost from birth. Despite being left parentless at the age of 15, the young genius had already been given private music tutoring and the chance to make friends with the family of Aga Khan.

Often lying his way through one adventure after another, Welles eventually settled in the Big Apple, where he shocked the world with a voodoo version of Macbeth, featuring a cast from the Negro Theater Unit of New York. His masterful radio work culminated in the Mercury Player’s famous “War of the Worlds” broadcast – so realistic that many went into a panic, convinced that Martians had invaded. This brought Welles only more fame and attention.

Hollywood’s RKO, excited by this new boy genius with the golden touch, offered him an astonishing contract. Now Welles, who had never worked in Hollywood, was going to write, produce, direct, and star in a motion picture masterpiece – Citizen Kane (1941), the famous, scathing profile of William Randolph Hearst.

Welles, only 25 at the time, felt fortunate to have legendary Gregg Toland as his cinematographer. When Welles asked the cameraman why he was willing to work with a kid, Toland famously responded, “Because you don’t know what can’t be done.”

The result was a masterpiece featuring a jarring flashback timeline, bizarre and innovative camera angles, deep focus (unheard of in those days), dramatic lighting, and a masterful use of sound. The film covered the life of Charles Foster Kane, his obsession with the much-younger Susan Alexander, and their obscenely large mansion called Xanadu. But even the simplest of minds could make the connections with William Randolph Hearst, Marion Davies, and San Simeon.

Hearst was furious and sought to have the original negative and all prints destroyed. He failed – and the film went on to make motion picture history.

Over in Italy, after the war, a new realism in cinema was born. Films such as Rome, Open City (1945) by Roberto Rossellini and The Bicycle Thieves (1948) by Vittorio De Sica featured low budgets, non-professional actors, and location shooting. Formalism was frowned upon. Italian neo-realism was born and would persevere into the 1960s.

In Japan, a young Akira Kurosawa was shocked to learn that his Rashomon (1950) had won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, despite the fact he had never submitted the film for consideration. Turns out that a person in Italy was impressed by the daring cinematography and varying plot lines and made sure it was screened. Despite being denounced by some in Japan as being too exotic and too “Western,” Rashomon was eventually hailed as one of Kurosawa’s greatest films.

In France, young moviemakers famously “invaded” the 1959 Cannes Film Festival. For years, these young men had written against a “safe” and formalistic approach to cinema, opting for risk-taking and experimentation. Hand-held cameras, grainy film stock, long takes, choppy editing, and stories that embraced radical social change were the order of the day. Francois Truffaut, a self-confessed “Paris brat,” started the ball rolling with The 400 Blows (1959). Eric Rohmer, Jean-Luc Godard and Claude Chabrol also made their contributions.

While the initial excitement of this French Nouvelle Vague had died off by the late 1960s, Rohmer succeeded in outlasting his contemporaries, making films into his old age. A devout Catholic, the director often explored the inability of characters to understand their own inner desires as they struggled with deep philosophical questions. His masterpiece, My Night at Maud’s (1969) was nominated for two Academy Awards. Rohmer made his last film in 2007 when he was 86 years old.

Going back to the 1950s – the old Hollywood studios that had ruled cinema for years now had to contend with this new approach to cinema. They also had to combat a new enemy – the box that delivered moving pictures into millions of family homes. Hollywood spectacles during the Golden Age of Television will be covered in our next article.

Note: After two weeks, this article will be archived under “A Brief History of Film” which can be located under “Articles, Essays, Blogs, and More” from the main menu.